Reflections #13: the era of nostalgia

Will we ever reminisce about Spotify Wrapped the way we reminisce about MTV?

In my head, 2002 is a hyper-grainy picture.

Actually, anything before 2010 is.

I was born in 1998, at the end of the millennium, the dusk of what is (to me) the nostalgia era.

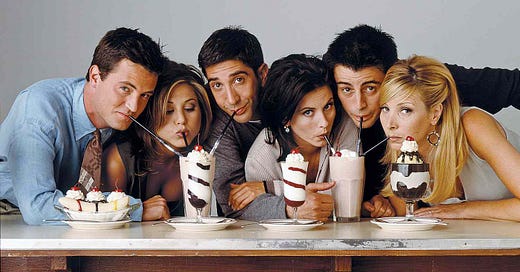

I am a seasoned fan of F.R.I.E.N.D.S, a newcomer to Girlmore Girls, but both these shows feel like yearning to me: I daydream of attending the live recording of the one where Monica and Chandler sleep together for the first time. Still, as a 26 year old, I would like to have the same experiences as Rory, aged 17, when she meets Lane in a cool but careless outfit to flip through a stash of hidden CDs.

I wonder if anything similar will ever happen to future generations looking back on current media. Maybe people born in 2025 will one day long for the non-AI IPhones their parents tell stories of, but will they watch an episode of Heartstoppers and desire - with all of their hearts - that they could have live-TikToked the series finale with their mates? Will they wish they could be the characters themselves, in all their retro glory?

I don’t believe that to be likely. Our media landscape, and consequently our media consumption habits, have been changing so significantly that I cannot imagine a future when anything produced beyond 2013 has remained relevant - if not iconic - for decades to come.

Our phones have been transformed to a powerful tool in the hands of advertiser-hungry big tech players, and that has permanently altered our approaches to new shows/movies/music and the impact these can have on pop culture, fashion and shared vocabulary.

Today, TV’s biggest competitor is not Netflix or one of the other streaming giants; for younger generations, the only palatable form of entertainment is TikTok (or whatever demonic version other social media platforms have created to compete with the hottest app on the market).

On there, trends don’t live long enough to become classics. How many viral moments have come and gone since 2020? None of them have left a real mark on culture. It’s not just the memes, the TikTok sound bites, moving at the speed of light, it’s the everything -core that belongs to everyone for a microsecond, until eventually some brand decides to join in on the trend thus declaring it dead.

It makes sense: our time-consuming apps are built to keep us there, showing us endless pages of content that racks up likes and views and comments. Everyone wants to be in on the inside joke, but the joke gets repetitive when everyone is copying each other off in hopes to get a taste of virality. Here’s where content creators come in, creating new content to set themselves apart from the masses, moving us along to the next big trend. Thus, the quick but sisyphean cycle is born: there’s always a hip new trend that becomes cringe the following second. Unlike a mid-season finale, which we had a couple of months to mull over, we can now forget all about what we were watching 12 hours ago.

But imagine that for one night you decide not to doom scroll: instead, you want to pick up a new movie, fresh on the shelves. It has become impossible.

There is so much offer on competing platforms that the choice you make when pressing play most probably depends on the market segment you belong to and what the algorithm believes would be kindred to your interests and values. Of course this remains true for social media platforms too, where our attention span is low and the only way to keep us engrossed is feeding us what technology knows either us or our peers have previously liked.

Essentially, a group of friends may all find their common lexicon made of TV show references and TikTok quotes, but the next group over - if they are of an ever so slightly different demographic - may exist without being able to eavesdrop on that conversation and understand it. By the time they catch on to its meaning, the world may have moved past it.

This is an evolution of popular culture that is significantly different compared to the ‘90s or the early 2000s, where the only limits were geographical and time lasted much longer. Not only did people mostly all watch the same thing, because that is what they could watch, but I remember when part of the fun was discussing what you had seen with your friends. It did help to have at least one week in between episodes. If you were prone to obsessive TV watching (like I was) this gave you a whole week to dissect the story frame by frame and imprint it into your young and impressionable skull.

Of course, sub-cultures were always a thing, and I am definitely talking of the mainstream here. But even the mainstream has become a puzzle of information now. Shows like F.R.I.E.N.D.S and Gilmore Girls, How I Met Your Mother, or Seinfield, shows that aired on general TV, were able to gain a reputation as icons of a culture each in its own era.

You could reference them with most people and - even if they did not watch it themselves - they would probably know what you were talking about.

Now, not only is the content never ending and it moving fast, but weirdly enough most of the people have no idea about it! Sure, a hyper-aware marketing manager in his late 40s might demand his brand be BRAT, but 75% of the office will not catch that reference.

Engrossed in our first watch of Gilmore Girls, my boyfriend and I have not yet managed to watch the newest season of the Bear. I was upset about it: surely I’d get spoilered, surely I would have FOMO.

Turns out, nothing at all happened!! I did miss out on one week of memes, but it lasted so little I barely had to worry about it.

This has everything to do with my nostalgic 1000th rewatch of F.R.I.E.N.D.S: I’m not only longing for the show itself, the high-waisted jeans and the witty comments, I am longing for the social experience that I will never get back.

There’s something else about media these days that prevents it from ever being a timeless classic.

When I was younger, I used to say my phone was an extension of my arm: no way I could go anywhere without it.

I realise now, more than a phantom arm, my phone is my phantom memory.

I store things in there - photos, poems, thoughts - outsourcing the damned thing to remember them. Potentially, the only reason why my memories appear to me in the form of the pictures on my first family album is that - thanks to technology - I don’t have to rely on my imagination of the past, I can just scroll through my camera roll.

I guess this is true for society at large: phones have become our collective memories, we rely on them to get information and to share information. Every single thing is documented.

This isn’t a bad thing: there is so much of the world we should all care about as humans, it is not fair to simply stare at your patch of green grass and assume the rest of the land is blossoming too. We are at a time where, when we are not educating ourselves about politics and current news, it must be a deliberate choice. We demand (whether rightfully or not) a certain level of awareness from what we are watching which renders it stuck in its own time and place.

Up until Netflix started having competitors, it feels like movies and TV series had to be able to speak to as wide an audience as possible, they did not have to find one specific segment to appeal to, because the whole world was their oyster. As mentioned above, these would be completely counterproductive for a new production: without a niche, they would cease to exist. This means that writers have to take a bigger political stance, if not in text at least in subtext.

Furthermore, even if as viewers from 2060 we were to watch something released in 2020, we would be able to browse the web or YouTube in reverse chronological order and discover what life was like back then across the globe, for people from all walks of life. This has created a new sensibility, where a show not even attempting to address the shortcomings of the time would feel embellished, but probably not good.

Nostalgia and reality don’t usually go hand in hand.

TV shows like F.R.I.E.N.D.S have become a white person’s archeological artifact: throughout those 236 episode, one can bear witness to what it meant to be young and white and thin in the 90s; it becomes an aspirational archive of what kind of life you were probably supposed to want. And because we don’t have vlogs from that time showing us first hand how truly bad life was in the ‘90s/2000s if you didn’t look like the protagonists, it becomes easier for someone like me - who is rediscovering these shows as an adult in 2024, having lived a comfortable childhood - to watch it and ache.

Imagine yourself once again as a viewer from 2060: if a piece of content set in 2020 was to completely gloss over COVID, a quick search on the web would tell you that they are wrong and a gazillion vlogs would show exactly how.

The spell would be broken.

Maybe the next generations will still feel nostalgic for a past they didn’t live through, because we are always prone to want what we learnt to crave and admire as children. But I don’t think it will be that easy, I don’t think that will be that much to be nostalgic over.

Super relatable article! I’m the same age as you, and much to my dismay I have personally seen a huge influx of nostalgia for 2014 and specifically the internet fandom era of it, so I don’t necessarily think the wide existence of social media in a time will lessen the nostalgia for said time. I think that the existence of social media actually heightens some longing for the past, almost like stumbling on an old diary in a thrift store. There’s a personal touch to looking at social media relics vs only having movies and TV as a time machine.

Culture has sped up to an alarming rate since COVID though, like the summers in the 2010s (despite having things like Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, Tumblr, Instagram, Snapchat, Vine, etc etc) had distinct cultural flavors that have been missing in the post-COVID years. Perhaps that is just me getting older and losing touch with the youth or perhaps it is, as you said, a collective transplant of our memories from our minds to our phones.

I’ve found a small antidote to it for me is to revisit analog media (polaroids, DVDs and CDS, sending letters) and making an effort to actively use it. Alongside watching TV from days gone by, it soothes the buzz social media causes in my head just enough to think more clearly. I’ve said for years I think smartphones will be viewed akin to cigarettes in the distant future. We can only hope the idea of having one in your hands at all times will be as foreign to our ancestors as smoking on planes is for us.